Notes on the Hebrew and Aramaic Language

Special Hebrew and Aramaic fonts are used throughout this article. To display the page properly you will need to have: 1)Estrangelo,

2)Levistam. You can obtain these from Dukhrana.com

Yeshua Meshikha and His Apostles and disciples all spoke Aramaic. When they were in the synagogue, the weekly Torah (Aurayta) and

Haftarah reading would be in Hebrew, followed by the Aramaic targum as was the custom probably since Nehemiah's time and still

the custom of Yemenite Jews to this day. (See Nehemiah chapter 8)

Hebrew and Aramaic Development

“Of all Semitic languages the Aramaic is most closely related to the Hebrew, and forms with it, and possibly with the Assyrian, the northern group of Semitic languages. Aramaic, nevertheless, was considered by the ancient Hebrews as a foreign tongue; and a hundred years before the Babylonian exile it was understood only by people of culture in Jerusalem. Thus the ambassador of the Assyrian king who delivered an insolent message from his master in the Hebrew language and in the hearing of the people sitting upon the wall, was requested by the high officials of King Hezekiah not to speak in Hebrew, but in the "Syrian language," which they alone understood (II Kings xviii. 26; Isa. xxxvi. 11).

In the early Hebrew literature an Aramaic expression occurs once. In the narrative of the covenant between Jacob and Laban it is stated that each of them named in his own language the stone-heap built in testimony of their amity. Jacob called it "Galeed"; Laban used the Aramaic equivalent, "Jegar sahadutha" (Gen. xxxi. 47). This statement undoubtedly betrays a knowledge of the linguistic differences between Hebrews and Arameans, whose kinship is elsewhere frequently insisted on, as for instance in the genealogical tables, and in the narratives of the earliest ages. One of the genealogies mentions Aram among the sons of Shem as a brother of Arphaxad, one of the ancestors of the Hebrews (Gen. x. 23). In another, Kemuel, a son of Nahor, the brother of Abraham, is called "the father of Aram" (Gen. xxii. 21). Other descendants of this brother of the Hebrew Abraham (Gen. xiv. 13) are termed Arameans; as, for instance, Bethuel, Rebekah's father (Gen. xxv. 20, xxviii. 5), and Laban, the father of Rachel and Leah (Gen. xxv. 20; xxxi. 20, 24). The earliest history of Israel is thus connected with the Arameans of the East, and even Jacob himself is called in one passage "a wandering Aramean" (Deut. xxvi. 5). During the whole period of the kings, Israel sustained relations both warlike and friendly with the Arameans of the west, whose country, later called Syria, borders Palestine on the north and northeast. Traces of this intercourse were left upon the language of Israel, such as the Aramaisms in the vocabulary of the older Biblical books.

Aramaic was destined to become Israel's vernacular tongue; but before this could come about it was necessary that the national independence should be destroyed and the people removed from their own home. These events prepared the way for that great change by which the Jewish nation parted with its national tongue and replaced it, in some districts entirely by Aramaic, in others by the adoption of Aramaized-Hebrew forms. The immediate causes of this linguistic metamorphosis are no longer historically evident.

The event of the Exile itself was by no means a decisive factor, for the prophets that spoke to the people during the Exile and after the Return in the time of Cyrus, spoke in their own Hebrew tongue. The single Aramaic sentence in Jer. x. 11 was intended for the information of non-Jews. But, although the living words of prophet and poet still resounded in the time-honored language, and although Hebrew literature during this period may be said to have actually flourished, nevertheless among the large masses of the Jewish people a linguistic change was in progress. The Aramaic, already the vernacular of international intercourse in Asia Minor in the time of Assyrian and Babylonian domination, took hold more and more of the Jewish populations of Palestine and of Babylonia, bereft as they were of their own national consciousness. Under the Achæmenidæ, Aramaic became the official tongue in the provinces between the Euphrates and the Mediterranean (see Ezra iv. 7); therefore the Jews could still less resist the growing importance and spread of this language.

Hebrew disappeared from their daily intercourse and from their homes; and Nehemiah—this is the only certain information respecting the process of linguistic change—once expressed his disapproval of the fact that the children of those living in mixed marriage" could no longer "speak in the Jews' language" (Neh. xiii. 24).

The oldest literary monument of the Aramaization of Israel would be the Targum, the Aramaic version of the Scriptures, were it not that this received its final revision in a somewhat later age. The Targum, as an institution, reaches back to the earliest centuries of the Second Temple. Ezra may not have been, as tradition alleges, the inaugurator of the Targum; but it could not have been much after his day that the necessity made itself felt for the supplementing of the public reading of the Hebrew text of Scripture in the synagogue by a translation of it into the Aramaic vernacular. The tannaitic Halakah speaks of the Targum as an institution closely connected with the public Bible-reading, and one of long-established standing. But, just as the translation of the Scripture lesson for the benefit of the assembled people in the synagogue had to be in Aramaic, so all addresses and homilies hinging upon the Scripture had to be in the same language. Thus Yeshua and His nearest disciples spoke Aramaic and taught in it.

When the Second Temple was destroyed, and the last remains of national independence had perished, the Jewish people, thus entering upon a new phase of historical life, had become almost completely an Aramaic-speaking people. A small section of the diaspora spoke Greek; in the Arabian peninsula Jewish tribes had formed who spoke Arabic; and in different countries there were small Jewish communities that still spoke the ancient language of their home; but the great mass of the Jewish population in Palestine and in Babylonia spoke Aramaic. It was likewise the language of that majority of the Jewish race that was of historical importance—those with whom Jewish law and tradition survived and developed. The Greek-speaking Jews succumbed more and more to the influence of Christianity, while the Jews who spoke other languages were soon lost in the obscurity of an existence without any history whatever.

Aramaic contributions to Jewish literature belong to both the eastern and the western branches of the language. West Aramaic are the Aramaic portions of the Bible, the Palestinian Targumim, the Aramaic portions of the Palestinian Talmud, and the Palestinian Midrashim.

In Palestinian Aramaic the dialect of Galilee was different from that of Judea, and as a result of the religious separation of the Jews and the Samaritans, a special Samaritan dialect was evolved, but its literature can not be considered Jewish. To the eastern Aramaic, whose most distinctive point of difference is "n" in place of "y" as the prefix for the third person masculine of the imperfect tense of the verb, belong the idioms of the Babylonian Talmud, which most closely agree with the language of the Mandaean writings.

The dialect of Edessa, which, owing to the Bible version made in it, became the literary language of the Christian Arameans -- bearing preeminently the title of Syriac -- was certainly also employed in ancient times by Jews. This Syriac translation of the Tanakh was made partly by Jews and was intended for the use of Jews*; and one book from it has been adopted bodily into Targumic literature, as the Targum upon Proverbs.

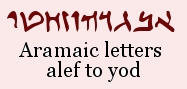

Among the Jews the two alphabets (Hebrew and Aramaic) co-existed side by side, though this by no means precludes the possibility that a writer, either from ignorance or inadvertence, may have occasionally inserted Aramaic letters into his Hebrew text, or vice versa. Such errors would occur especially when the parallel letters differed very slightly.

According to both Jewish and Christian tradition, the introduction of the Aramaic script and its use for the Holy Scriptures are directly attributed to Ezra the scribe (see Sanh. 21b, 22a; Yer. Meg. 71a; Origen, ed. Migne, ii., col. 1104: Jerome, "Prologus Galeatus"). The former statement is certainly not correct; nor can the latter be established satisfactorily. Supposing the introduction of the Aramaic script to have taken place in the fifth century or even later, the older manuscripts would hardly have been destroyed on that account. At all events, this much is assured, that, irrespective of the Samaritans, the knowledge of the older script still existed among the Jews for several centuries (Meg. ib.; Origen, "Hexapla" on Ezek. ix. 4, quotes the testimony of a converted Jew).

”

-- From the Jewish Encylopedia, 1906, public domain, with some corrections and minor changes in spelling.

The Aramaic Peshitta

“In the Mediterranean regions of the Roman Empire, the new Covenant writings of the Gospels, Acts, Epistles and Revelation were handed down in Greek, lingua franca of the West. In the Holy Land, Syria, Mesopotamia, and other countries of the Parthian Empire, these writings were circulated in Aramaic, lingua franca of the East. The apostles and disciples obeyed the command to proclaim the tidings of the kingdom of God. this they did in the Holy Land and the diaspora communities throughout the empires of Rome in the West, and of Parthia in the East. For this goal they had at their disposal the two international languages of their times, Greek and Aramaic, through which they reached their people, Jews and Israelites, and the nations in those two realms (Matthew 10:16; 28:19; Acts 2:9-11)...

The main vernacular in the Holy Land... was Aramaic. The weekly synagogue lections of the Holy Scriptures, called sidra or parashah, with the haphtarah, were accompanied with an oral Aramaic translation, according to fairly fixed traditions. A number of Targumim in Aramaic were thus eventually committed to writings, some of which are of unofficial character, and of considerable antiquity.

The Mishnah, completed towards the beginnings of the third century A.D., the Tosefta, and early Midrashim, were all written in Hebrew. The Gemara of the Jerusalem Talmud was written in Palestinian Aramaic, and received its definitive form in the fift century. The Babylonian Talmud with its commentaries on only 36 of the Mishnah's 63 tractates, is four times as long as the Jerusalem Talmud. These Gemaroth with much other material were gathered together towards the end of the fifth century, and are in Eastern (Babylonian) Aramaic. Since 1947 approximately 500 documents were discovered in eleven caves of Wadi Qumran near the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. In addition to the scrolls and fragments in Hebrew, there are portions and fragments of scrolls in Aramaic. Hebrew and Aramaic have always remained the most distinctive features marking Jewish religious and cultural life to our present time.

In the Greek text of the New Testament one finds Aramaic locutions in disguise, in addition to several words and phrases in Greek transcription... indicating that Yeshua spoke in Aramaic, and no doubt used Hebrew in conversations with scribes and other religious leaders, in addition to the synagogue use of Hebrew.

”

--Extracted from the Editor's Note in the New Covenant Aramaic Peshitta Text with Hebrew Translation published and copyright

1986 by the Bible Society of Israel and the Aramaic Scriptures Research Society in Israel.

Change in Pronunciation and Script

The original Aramaic New Covenant Scriptures were likely written with the so called "Herodian script" -- the same script used in the Habakkuk Pesher found among the Dead Sea

Scrolls.

The original Aramaic New Covenant Scriptures were likely written with the so called "Herodian script" -- the same script used in the Habakkuk Pesher found among the Dead Sea

Scrolls.

We know the Estrangela script is very ancient and this is what the Peshitta has been written in for a very long time. The

Estrangela script, while ancient, is still not the original that was used in composing the Peshitta. When the Church of the

East took over the Peshitta and began making copies for use by the churches, they used the Estrangela script, and the originals

were respectfully destroyed according to tradition. In a forum post, Paul Younan, native Aramaic speaker, said,

"I've actually been told by a number of priests that Estrangela came later, like Swadaya that we use today with vowel

points, or the Serto of the Jacobites."

My great grandfather made extensive lists of words and phrases in Aramaic that someone (likely my father or one of his associates)

later wrote in the English equivelant for most words. The words are almost identical to the Aramaic text of the Peshitta but

differ in some of their spellings due to the minor differences between the Christian and Jewish dialects*. The glossary is dated 1913 with the English text being dated to 1967. He stated, "These words are from the holy word written in our language."

I am exploring this further and will update this article accordingly.

* "The Peshitta translation of Genesis, and indeed of the Pentateuch as a whole, is particularly rich

in links with contemporary Jewish exegetical tradition, and this makes it likely that these books were translated by Jews rather than by

Christians.... the Peshitta translation of Proverbs is also likely to have been the work of Jews in northern Mesopotamia; it subsequently came to

be taken over by Syriac-speaking Christians and by later Jews (who lightly modified the dialect)"

(The Bible in the Syriac Tradition, by Sebastian Brock)

Copyright © 2007-2010 HebrewAramaic.org, Ya'aqub Younan-Levine. Bibliotheca Aramaica

Original design by Steves Templates

|